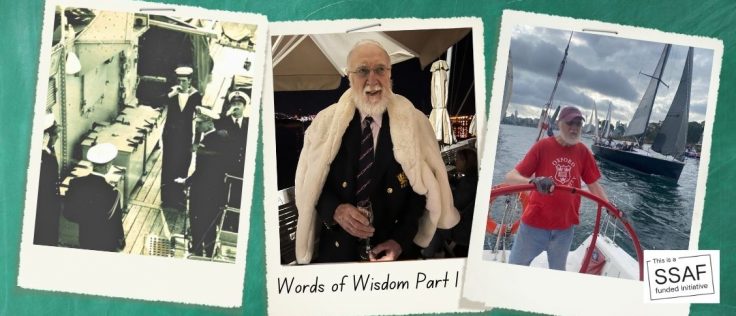

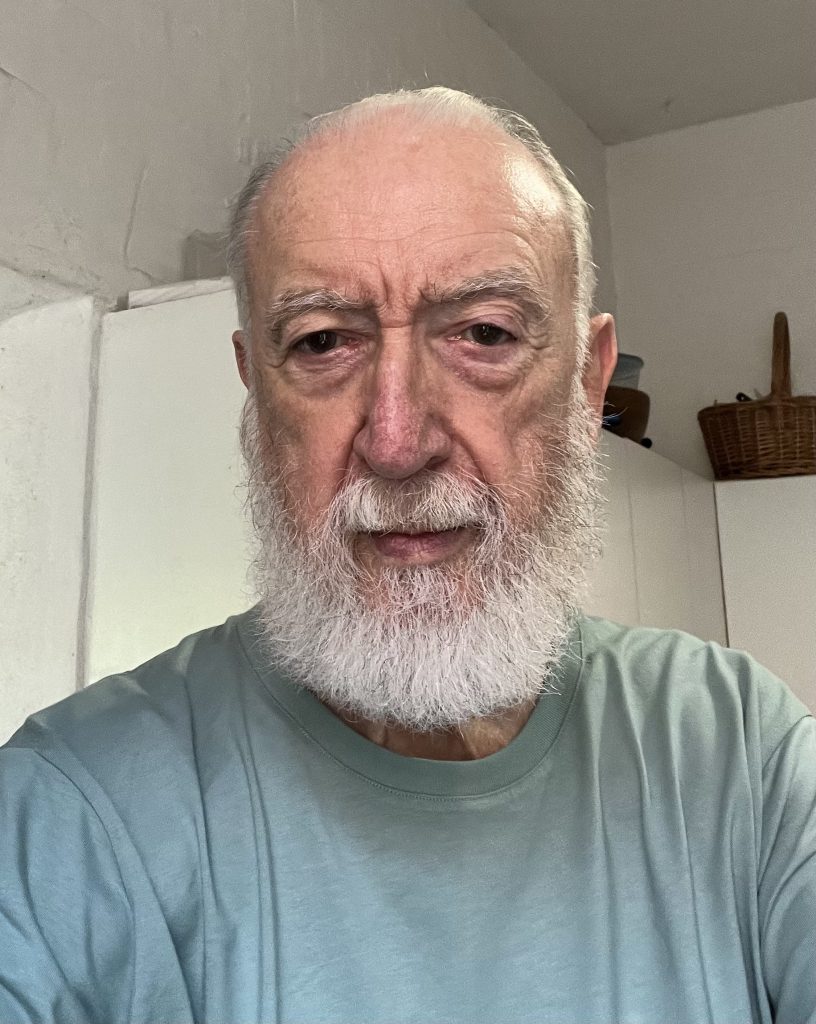

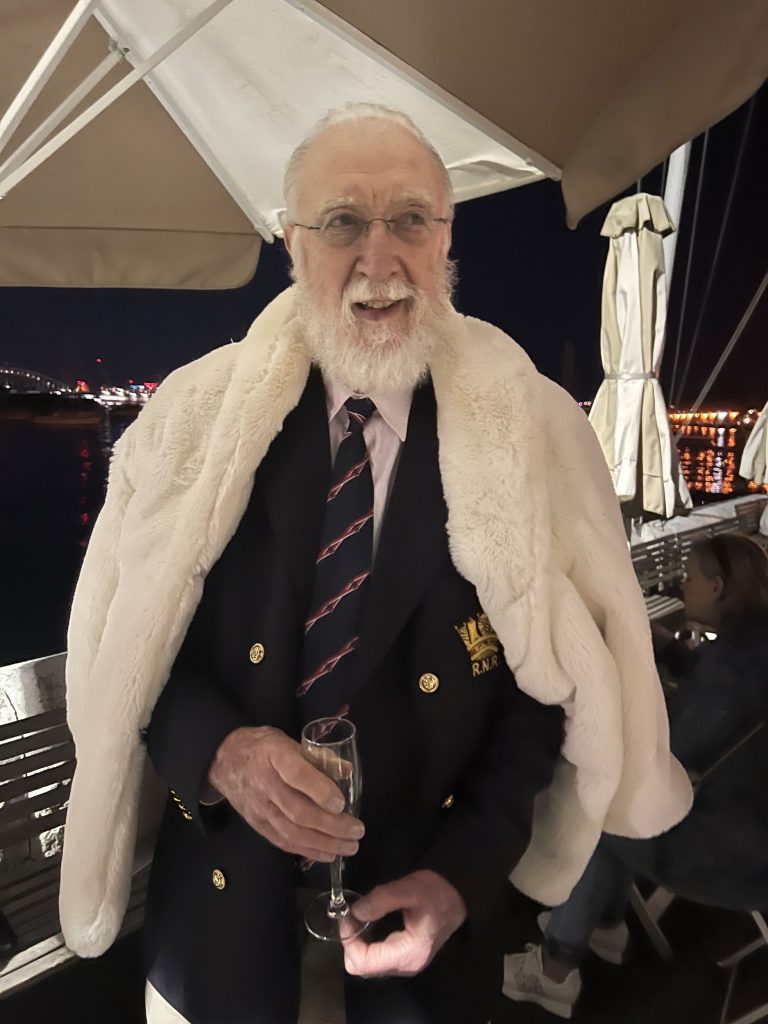

Written by Theresa Arden

“If you’re over 60 and not madly in love, it might be time to call your undertaker.”

The enduring wisdom of Associate Professor Latimer – educator, philosopher, and sailor.

At 86 years young, Associate Professor Latimer is far more than a long-serving academic—he’s a philosopher at heart, a former naval reservist, a competitive sailor, and a lifelong student of life, love, and learning. Born in Belfast in 1939, he spent his early years surrounded by war and austerity, eventually serving five years in the UK Royal Naval Reserve. Before migrating to Australia in 1962, he worked in jobs as varied as van driving and construction in the French Alps.

His academic path, which began with modest grades, evolved into First-Class Honours, a PhD, and a medal. Alongside that, he became a passionate sailor and later, a proud grandfather. Since 2009, he’s also been a mainstay of CSU’s School of Psychology, quietly shaping minds, championing argument over anecdote, and reminding us all that learning never ends.

“I’ve never really stopped learning—or teaching,” he says. “I just keep finding different ways to do both.”

In this blog, Latimer shares reflections on teaching, technology, academic integrity, and the little things that keep life meaningful.

Redirection

“I didn’t retire—I redirected.”

After officially retiring from the University of Sydney in 2002, Latimer embraced what he calls “the retiree starter pack”—a bit of travel, a boat, regular listening to ABC Radio National, and time spent gazing out the window. But the quiet didn’t last.

After a few years, he was drawn back into academia by Central Queensland University, where he began marking and supervising Honours projects. Then, in October 2009, a former University of Sydney colleague, Dr Robert Buckingham, a lecturer at CSU, offered him marking work in his courses.

“This expanded to lectures at a Bathurst Summer School, Honours and Postgraduate supervision, and marking.”

One of Latimer’s most memorable contributions from those early years was his involvement in the “Being a Student Project” in 2013–14, which focused on critical thinking, argument mapping, and academic writing. Though the initiative was eventually discontinued, he’s now turning his contributions into a forthcoming book titled How to Write Psychology Essays and Laboratory Reports.

“These are skills that are sadly lacking in the majority of students I teach at CSU.”

His most sustained contribution over the past 15 years has been coordinating PSY101 Bathurst Distance—a role that has left a lasting mark on the School of Psychology’s teaching program.

“It’s work that matters,” he says. “These are skills that too many students lack—but they’re absolutely essential.”

AI – A Blessing and a Curse

“If you’re thinking of using ChatGPT to write your assignments in my class – be afraid”

Latimer’s relationship with artificial intelligence goes back more than 50 years. During his PhD in the 1970s, he spent a year at the Bionics Research Laboratory School of Artificial Intelligence, University of Edinburgh, working alongside some of the early pioneers in the field, including Seymour Papert from MIT.

He speaks passionately about AI’s potential but draws a sharp line when it comes to misuse—particularly by students seeking a shortcut.

“I’m a supporter of AI,” he says. “But I don’t take kindly to its misuse—especially by students who don’t understand what they’re doing and want a free pass on their assignments.”

For Latimer, using AI without understanding the underlying material undermines the entire purpose of learning. He makes it clear that critical thinking and clear communication aren’t optional in his classroom—they’re the core of what students are here to develop.

Old School Habits

“We love stories—but arguments are what matter.”

When asked what “old school” habit he refuses to let go of, Latimer doesn’t hesitate: critical thinking. For him, the ability to analyse arguments—not just accept them—is fundamental to education, public discourse, and life itself.

“The one major habit we all should acquire, maintain and apply in all situations is to think deeply and critically about all arguments we encounter, including our own,” he says. “We must tease out their premises and examine closely and relentlessly their chains of inference, and whether or not their conclusions are substantiated.”

It’s not an easy task, he admits. We live in a narrative culture—one that’s more comfortable telling stories than building reasoned arguments. He often sees this play out in student essays that summarise reading rather than take a position.

But the problem extends far beyond the classroom. Latimer notes that even national leaders fall into the trap of weak or non-existent reasoning.

“For example, a President of the USA, land of the free and home of the brave, initiating a tariff war without any pellucid substantiating argument for doing so, and within hours, having second, third and fourth reservations. As we have seen in very recent days, an aspiring Australian Prime Minister demonstrating total ignorance of the science substantiating theories of climate change and resorting to sloganeering and unargued energy policies.”

Charlie blog is a SSAF funded initiative.